Ken Kaplan

One of the earliest, continuous technology disrupters and innovators who found IPO success

In the late 20th century, the personal computer revolutionized the world, opening up endless possibilities for technologists and dreamers across the US. Iowa, often overlooked in the tech landscape, was no exception.

A startup is a giant company that doesn’t know it yet - Paul Graham

What you’re reading now began as a book project. I was seeking to document the history of technologists who laid the foundation of tech companies in Iowa and paved the way for modern day startup founders. I wanted to go well before 2010, the unofficial launch of the startup era in Iowa. All roads first led to Ken Kaplan.

Ken, a consummate inventor and technologist, is my earliest record of a successful startup (before startups were a thing) CEO in Central Iowa. Although the original 1977 filing for his company, Microware, at the Iowa Secretary of State is no longer publicly visible, the 1986 refiling of its articles bears his signature, sufficient proof for me of its provenance.

Ken was joined by two other engineers in 1977 to start a company based upon research inspired by the National Science Foundation. They would go on to build a real-time operating system, a class of software that needed to be small, fast, predictable and could be embedded into other devices. They built an expertise on the new microprocessors being built by Motorola and Intel for multiple industries, including consumer electronics, medical devices, telecommunications and the military.

A friend once described the RTOSs as software that could be embedded into a television to decode and display the broadcast signal, or to be embedded onto a chip in a satellite receiver box to receive an encrypted signal, validate if the subscriber had rights to a channel, and pass on an unencrypted video to the TV. Similarly, RTOSs enabled the industry of cellular phones (even the brick-sized bulky devices), weapons systems, and more. They, thus needed to be small and highly efficient, rendering thier development to a small set of engineers and programmers often able to think in Assembler or tightly compiled (vs interpretive) programming languages.

I first encountered Microware during a Friday afternoon celebration in 1993. The engineers, who would later become close friends, were enjoying BBQ and drinks, showing me their elegant work written in C and assembler. One showed me how he’d spent weeks (months?) shaving bytes off his compiled code so it could fit within 48KB to meet manufacturer specification and desired scale.

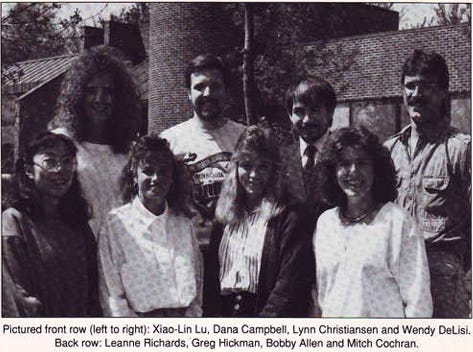

Unlike my corporate IT job at the time and elsewhere, Microware had already adopted a relaxed atmosphere that wouldn’t become normalized at tech companies for at least another decade. Ties were nearly non-existent, and people were proud of their code and its destination. I share a rare photo from a company newsletter which happens to include another friend, Greg Hickman, below.

Ken led the teams from its original 3 to nearly 175 at the time of their IPO in 1998. Microware had not only successfully deployed itself into millions of devices, it had also built a repertoire of its own intellectual property. They’d built an entire operating system, OS-9, their compiler written specifically to produce efficient and tight software for embedded devices, plug-ins and add-ons that provided networking via standard and proprietary protocols, and much more.

OS-9 was not just another operating system, it had a large following due to its compact size, Unix-like structure, and a large community. Technologists will reminisce at some of the code samples and discussions in this company magazine/newsletter circa 1992.

In addition to OS-9, another flagship product DAVID (Digital Audio Video Interactive Decoder) helped accelerate the adoption and distribution of digital TV. Though digital signals today are the norm, the mid-1990s required an add-on box to decrypt and convert digital signals for use by analog TVs. Microware built such add-on boxes. Microware and its engineers, led by Ken, were ahead of their time. That leadership foretold the impact Microware’s diaspora would continue to have on the industry.

Over lunch, I sought to understand from Ken why he created such a company in Clive, Iowa when common sense should’ve driven him to Silicon Valley. After all, in the preceding decade, another notable Iowan, Bob Noyce had cofounded Intel after an incredibly celebrated careers and inventions at Shockley Semiconductor Laboratory and Fairchild Semiconductor.

His answer was immediate and clear - the large number of engineers and professional software developers coming from regional and national universities demonstrated a strong work ethic coupled with significant talent. Social media had yet to divert many of their attention toward “worthless apps” and many took pride in creating magic from hardware using software. They were tinkerers and hackers (in its original meaning), able to squeeze more out of hardware than specifications supported.

Microware’s growth continued through the Internet era and digital TV proved to be a worthwhile investment. The welcome mat rolled out to technology companies since the Internet’s public availability in the mid-90s extended a capital structure to facilitate Microware’s growth as well.

Microware shifted from a privately held company and offered an IPO. It went public (I was able to be an IPO shareholder) in April 1996 and operated as a public company until September 2001. A different market condition existed post Internet boom in 2000s, and the company was acquired by Radisys Corporation to return to a privately held structure.

This inflection point in Microware’s history is significant.

Both the IPO and the Radisys acquisition provided meaningful exits to many engineers. Several would convert their newly earned wealth into a well-deserved early retirement. Yet others would seek consulting roles or other employment to continue their technology careers. A select number became technology entrepreneurs and evangelists of embedded systems themselves. I will share one such entrepreneur, dear friend, and his product in a later story.

Ken could have, but did not retire to go golfing into the sunset. Much as his customers then and now, he continues to learn something new every day. During our discussion, he was studying the history of technology with an emphasis on 19th and 20th-century science and engineering. He is inspired by inventors and emergent technologies. On the day of our conversation over buffalo wings and bar food, Calculus reigned top of his mind.

Ken Kaplan's entrepreneurial journey from a small startup in Clive, Iowa, to a successful public company is a testament to the power of innovation and community. His continued learning and scientific pursuits continue to inspire engineers and entrepreneurs in Iowa and beyond.

Ken Kaplan is the Chief Scientist of Microwave technology at Crescend Technologies and continues to work in the Des Moines metro area. I enjoyed this conversation and catch-up with him over lunch one afternoon and my discussion notes are likely affected by a mix of a great lunch and insightful conversation.

Sources-

Conversation with Ken Kaplan, Whisky River, Ankeny, August 2024

Microware - Wikipedia

Chicago Tribune, 1989

LA Times, 1994

Wired, 1994

I am a proud member of the Iowa Startup Collective, a group of writers exploring entrepreneurship across Iowa. Please check out my peers at this column roundup